Want more housing market stories from Lance Lambert’s ResiClub in your inbox? Subscribe to the ResiClub newsletter.

Speaking Tuesday at the National Association for Business Economics meeting in Philadelphia, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell offered his clearest reflection yet on the Fed’s pandemic-era mortgage bond buying.

He acknowledged that the central bank may have kept purchasing mortgage-backed securities (MBS) for too long—but he also suggested that those purchases may have had a smaller effect on the housing market’s trajectory than some assume.

“Regarding the composition of our purchases, some have questioned the inclusion of agency MBS purchases given the strong housing market during the pandemic recovery,” Powell said. “The extent to which these MBS purchases disproportionately affected housing market conditions during this period is challenging to determine. Many factors affect the mortgage market, and many factors beyond the mortgage market affect supply and demand in the broader housing market.”

“With the clarity of hindsight, we could have—and perhaps should have—stopped asset purchases sooner,” Powell continued. “Our real-time decisions [in 2020-2021] were intended to serve as insurance against downside [economic] risks [following the pandemic].”

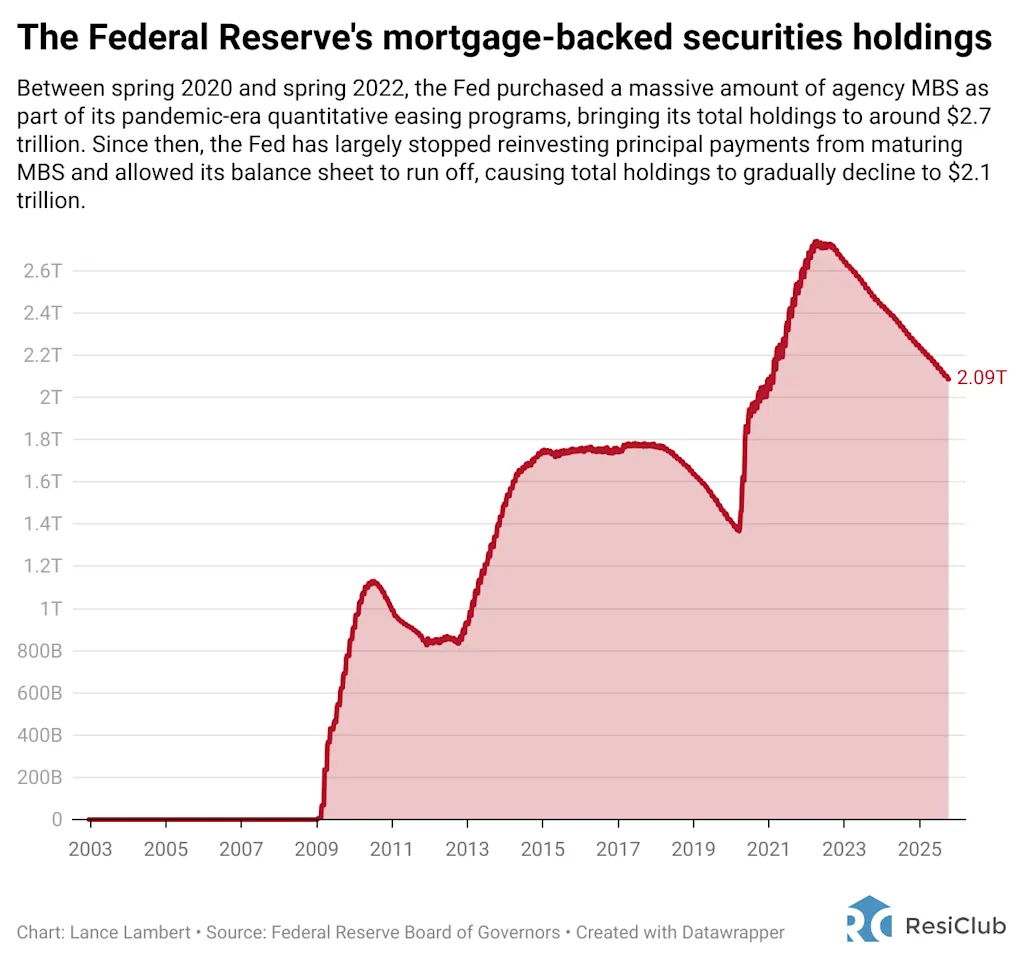

From 2020 through 2021, the Fed was purchasing hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Treasuries and MBS. Those actions—part of its quantitative easing (QE) program—were designed, in theory, to lower long-term borrowing costs and support financial stability at a time when the policy short-term rate was also pinned near 0%.

When the Fed buys long-term bonds like Treasuries or MBS, it creates extra demand for those securities. When bond prices rise—say for MBS—then the yields—or mortgage rates for MBS—fall. They move inversely.

Critics have argued that those MBS purchases added unnecessary fuel to a housing market already running red-hot during the Pandemic Housing Boom. They contend that by continuing to buy MBS deep into 2021, the Fed artificially suppressed mortgage rates—with the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate hitting an all-time low of 2.65% in January 2021—and helped intensify competition among buyers, worsening affordability.

Powell’s comments on Tuesday acknowledged, to a small degree, an element of that critique, but also suggested that the actual impact may have been smaller than many assume. He appeared to imply that other powerful factors—such as the pandemic-era surge in demand for more space, the unlocked “WFH arbitrage” (including the domestic migration wave it triggered), and pandemic-era savings—were also at play. Of course, Powell has repeatedly stated that he simply believes there aren’t enough homes in the country.

While the Fed can’t undo its 2021 asset purchases, Powell acknowledged that, going forward, the central bank could be “more nimble” in adjusting its balance sheet—hinting that future QE programs might be shorter or more targeted.

“Stopping [QE asset purchases, including MBS] sooner could have made some difference, but not likely enough to fundamentally alter the trajectory of the economy,” Powell said on Tuesday. “Nonetheless, our experience since 2020 does suggest that we can be more nimble in our use of the balance sheet, and more confident that our communications will foster appropriate expectations among market participants given their growing experience with these tools.”

No appetite for using MBS to address the current housing strain

Some online observers—let’s be honest, mostly those tied to the mortgage and housing industries—have floated the idea that the Fed could start buying MBS again to help bring down today’s elevated mortgage rates.

But when asked on Tuesday whether renewed MBS purchases might be used to improve housing affordability, Powell firmly rejected the notion.

“We look at overall inflation, we don’t target housing prices. And we’d certainly not engage in mortgage-backed security purchases as a way of addressing mortgage rates or housing directly,” said Powell. “That’s not what we do.”